Ecumenopolis: City Without Limits. Directed by Imre Azem. Turkey and Germany, 2012.

Almost exactly a year before the current protests in Turkey—commonly referred to as “Occupy Gezi,” after Gezi Park, located in the Taksim neighborhood of Istanbul—a film called Ecumenopolis: City Without Limits was screened in the very same park. The event was announced as a public premiere, and it was co-sponsored by two groups. The first was the Taksim Coalition, comprised of concerned city planners, architects, local business owners, and activists. The second was the Istanbul chapter of the Chambers Union of Turkish Engineers and Architects (TMMOB), an outspoken critic of the physical transformation of Istanbul under the current government.

During the writing of this review of Ecumenopolis, the governing Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP) branded the Taksim Coalition one of the main culprits of the ongoing protests in Turkey. Dozens of its members were arrested and held in custody for days. Meanwhile, during an overnight emergency session in the parliament, the TMMOB was practically dismantled by the AKP. The government revoked its autonomous status and rights to supervise and investigate building projects in Istanbul.

Viewed through this prism, one would expect Ecumenopolis to contribute crucial insight into the well-documented atmosphere of civil disobedience in Turkey, and the film does not disappoint. Ecumenapolis focuses on a key grievance of the people of Istanbul: the continuing deterioration of the state’s respect for their existence. Director Imre Azem also refutes a common trope used to explain the current protests in Turkey: that they have been initiated by an urban middle class elite who want to live a secular and Western lifestyle, and thus they do not represent a significant proportion of the Turkish population. Although it pushes back against this idea, the film does somewhat marginalize the fact that the AKP government is a symptom rather than the cause of the grievance the film portrays: the barbaric destruction of Istanbul, as well as other metropolises of Turkey, that have been taking place since the 1960s.

Ecumenopolis, which is Azem’s first feature-length documentary, depicts the changing landscape of Istanbul during the last decade. It offers a visual critique of the transformation of the city at the hands of neo-liberals and other advocates of globalization. It is concerned with both the ecological and the human cost of the city’s redevelopment schemes, and it leaves the audience with a bitter taste indeed.

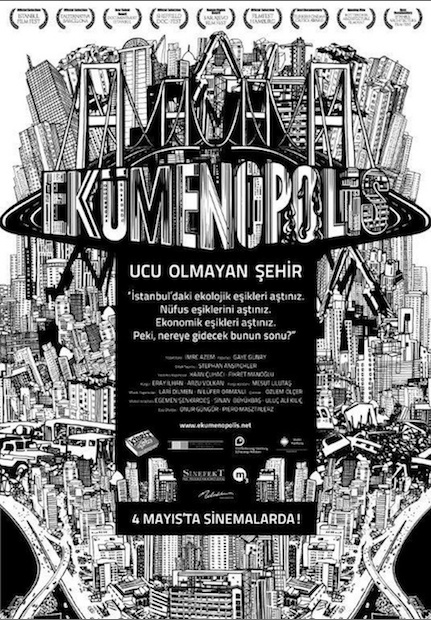

[Poster for Ecumenopolis: City Without Limits]

Throughout the film, Azem looks at the lives of the ordinary people who lack the means to defend themselves in a war waged upon them by a coalition of government and private companies in the name of profit. The landscape depicted in Ecumenopolis is mostly one of construction sites, industrial areas, shantytowns, and empty lots. When the camera wanders into more established neighborhoods, it does so in order to document the lives of people waiting for the demolition of their neighborhoods. On the margins of this bleak Istanbul, we catch glimpses of a prettier city—one that seems to offer a better life, but also suffers from its own problems, like water shortages, traffic jams, and poor public transportation.

Throughout Azem’s interviews with city planners, architects, developers, and ordinary residents, the Housing Development Administration of Turkey (TOKI) emerges as the main agent of Istanbul’s urban transformation. TOKI has been engaged in a social housing unit building spree for over a decade, and those who are familiar with Turkey know the institution from its tall, unsightly buildings painted in shades of pink, taupe, and pistachio, often surrounded by high walls. It regularly appropriates land and property for development from both public and private titleholders, under the pretext of being either illegally possessed, unfit for occupation, or in need of redevelopment.

TOKI argues that Turkey needs to create approximately three million new housing units over the next five years to meet demand. In order to achieve this goal, it has built some six hundred thousand housing units during 2012 alone. Meanwhile, those who are critical of TOKI, such as the TMMOB, argue that approximately seven hundred thousand units currently remain empty in Turkey, including roughly four hundred thousand in Istanbul. This sales lag is not solely due to the economic slow down. People neither need nor want to live in these houses. One result is the emergence of “ghost towns,” as one expert calls them. Turkey, it seems, is heading for a council housing crisis of its own—like the ones that destroyed the cultural fabric of the UK and France—or a future spree of urban demolition at the expense of taxpayers, as happened in Denmark and Germany. In fact, Azem’s next documentary, Agoraphobia, due to be released later this year, focuses on these ghost towns mushrooming in Ankara, Bursa, and Izmir, as well as Istanbul.

Azem’s attention to TOKI’s monopoly over the urban housing terrain also fuels his larger criticism of the AKP’s neo-liberal economic policies. In an interview with Mücella Yapıcı, the secretary of the TMMOB and a member of the Taksim Coalition who spent two days in jail last month, we hear how, during the late 1990s, the World Bank instructed Turkey to designate at least one metropolis as its chosen global financial center. The obvious choice was Istanbul, and the AKP fully embraced this idea upon coming to power in 2002. (The literature regarding the AKP’s neo-liberal sympathies is well established, both in book form and in recent commentaries.) Wishing to transform Istanbul and Turkey according to World Bank and IMF standards, the AKP privatized Emlak Bankası (the State Housing Bank), and then closed it, along with Arsa Ofisi (the State Land Offices), in 2004. Their roles in the provision of subsidized loans and affordable housing were later centralized under TOKI. Finally, the law covering TOKI’s duties was rewritten to make it a profit-making institution.

Today, TOKI oversees the re-possession and transfer of state properties (both inhabited and uninhabited); their subsequent allocation for development; project planning; the hiring of private construction firms; and the administration of sale upon completion. More controversially, its profits are often transferred into so-called “disguised budgets” (örtülü ödenekler) and used to pay for secret government activities that cannot be paid through official budgets, including the war on “terrorism,” aid to the Syrian rebel army, and covert operations against the Kurdish insurgency, to name just a few.

Although Ecumenopolis touches upon the environmental problems of Istanbul’s transformation—such as deforestation, water scarcity, the destruction of public spaces, and the lack of mass transportation—the artificial housing crisis and its consequences remain its main subject. To reveal the human costs of this urban transformation, Azem examines the experience of Kasım Aydın and his family, who lost their house to developers through one of the urban transformation schemes supported by TOKI. Their example challenges the claims of those such as Francis Fukuyama, Anthony Faiola, and Paula Moura, who suggest that the Gezi Protests are a form of civil disobedience led by the urban, secular, middle class against an Islamist neo-conservative government. The story of Kasım Aydın suggests that there is something more at work here, something beyond class and religious divides, which may have been one of the main reasons why nearly 2.5 million people took it to the streets during the month of June, in seventy-eight out of eighty-one Turkish cities.

Azem narrates the story of Kasım and his family roughly from 2002 to 2011, during which time they become victims of an urban transformation scheme. The Aydıns are neither middle class, nor secular, nor city folk. They are conservative, religious, and rural. One sign of this is how Kasım’s wife remains nameless throughout the film and never speaks to the camera. The family immigrated to Istanbul in search of work and settled in Ayazma, a neighborhood in İkitelli, where they were surrounded by families just like themselves. They were, in other words, ideal candidates to vote for the AKP. Residents complain that the district of İkitelli—comprised mostly of factories and shantytowns— is largely ignored, except for election years when politicians seek their votes.

The year 2002 represents a turning point for Ayazma, not just because the AKP came to power, but also because an Olympic Stadium was completed that year, not far from Kasım Aydın’s house. The area then became a site of real estate speculation. Kasım’s house was demolished when TOKI handed over Ayazma to Ağaoğlu Holdings. Although residents collectively bargain with TOKI for homes in a far-away housing project, construction lags for two years and the cost rises thirty percent. Instead, the Aydın family moved to another neighborhood, which appears to be another candidate for a TOKI appropriation. Kasım now commutes long hours to work and his two children lose the prospect of a proper education.

Azem intersperses his interviews of Kasım with interviews of Ali Ağaoğlu, the owner of the company that destroyed Kasım’s house. What emerges is an indirect dialogue between the dispossessed and the colonizer. Kasım says he wants good housing near his work. But Ali, confusing democracy with capitalism, argues that one must pay the price for what one wants in a free democratic society. There is no question on whose side the AKP stands: not its traditional electoral base—the poor immigrants who come to the city for work—but rather members of the privileged upper class who abuse them.

Sadly, this is not the only story that can be told of appropriation and dispossession. Ayazma is not the only neighborhood destroyed. Sulukule and Tarlabaşı—other poor and working class neighborhoods in Istanbul—also met the same fate. Last year, Azem produced a short film called Sulukule: Transformation for Whom? directed by Nejla Osseiran. This film ties his body of work together into a larger argument. Similarly, the trailer of his next film, Agoraphobia, suggests that Azem will pick up on the story of Tarlabaşı, which is mentioned only in passing in Ecuemonpolis.

Today, a Turkish citizen’s right to housing is not formally guaranteed by the constitution, but rather deduced from other rights, such as the right to own, rent, cultivate, and develop property, or the right to lead a decent life. Surely, as a majority government, the AKP could have corrected this discrepancy during the last decade had they so desired. Nevertheless, it is important to remember that the AKP is not the first Turkish government to fail its citizens in this regard, just as Ecumenopolis is not the first film to bring the subject to the big screen. İpek Türeli’s recent article, “Istanbul in Black and White: Cinematic Memory,” notes how the film Otobüs Yolcuları [Bus Passengers], written and directed by Vedat Türkali in 1960,

critiques the power relations that were operating within the construction sector, which, as one of the leading sectors within the urban economy, seems to have created its own social groups. It aims to expose the stench of capitalist relations, in particular how modest people living on the margins of the city were conned by a power coalition between politicians, capitalists, and technocrats with promises of access to modernity through housing.

Over fifty years later, Azem is treading the same ground, revealing this to be an endemic problem, rather than one that has recently emerged. But aside from a short cartoon entitled “An Istanbul Story,” which opens Ecumenopolis, Azem barely explores the historical roots of Istanbul’s destruction. His criticism of the AKP also applies to previous governments, such as Adnan Menderes’ Democrat Party (1950-60) and Turgut Özal’s Anavatan Party (1983-93), but the film does not situate the current situation within that broader historical context. This being said, there is no doubt that in its search for power, the AKP followed the neo-liberal policies prescribed by the World Bank and the IMF, to the degree that during this year, it was allowed to pride itself for having paid the nation’s debt to these institutions, as well as to loan five billion USD in order to gain the status of donor and pose as a G20 nation. More ironically, this alliance is one of the main reasons why the AKP is suffering today from the same crisis of legitimacy as its friends, as explained by Jürgen Habermas and Alain Badiou, to name just two.

As a debut documentary, and under the current circumstances, Ecumenopolis deserves much attention. It successfully depicts a city and a population with growing grievances against the AKP. In one scene, in the neighborhood of Sulukle, a sign hanging on a building waiting to be demolished reads: “Bulldozer operator: Sevil lives as a tenant in this building and she is blind, please knock before you destroy it.” Graffiti on a wall across from Kasım’s house asks: “Are we going to enter the EU by exploiting the poor?” And a resident whose home is about to be destroyed states shortly and simply: “We want to live and die where we were born and grew up.” It is not a figment of our imagination that these are some of the same people who supported the Occupy Gezi movement during its emergence and growth into a national phenomenon.

![[Still image from \"Ecumenopolis: City Without Limits\"]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/eco_new.jpg)